Vitaly Bulgarov

With more than 15 years in the industry, Concept Designer and a 3D Artist, Vitaly Bulgarov has developed not only a deep affection for cutting edge technology, innovation and inspiring futuristic design, but also, an impressive resume working in film, video games, and industrial design for real products. Bulgarov has collaborated with industry giants such as Dreamworks, Blizzard Entertainment, LucasFilm’s Industrial Light&Magic, Paramount Pictures, MGM, and Skydance Productions. As a conceptual and industrial designer, Bulgarov contributed to projects for Intel, Boston Dynamics, Panasonic, Microsoft, and Oakley. Currently, Vitaly Bulgarov works as a Principal Designer at Hankook Mirae Technology while also developing the side-scrolling survival action game, Machine Instinct, as well as an unannounced dark fantasy action RPG. To learn more, visit: Vitalybulgarov.com and MachineInstinct.game

With more than 15 years in the industry, Concept Designer and a 3D Artist, Vitaly Bulgarov has developed not only a deep affection for cutting edge technology, innovation and inspiring futuristic design, but also, an impressive resume working in film, video games, and industrial design for real products. Bulgarov has collaborated with industry giants such as Dreamworks, Blizzard Entertainment, LucasFilm’s Industrial Light&Magic, Paramount Pictures, MGM, and Skydance Productions. As a conceptual and industrial designer, Bulgarov contributed to projects for Intel, Boston Dynamics, Panasonic, Microsoft, and Oakley. Currently, Vitaly Bulgarov works as a Principal Designer at Hankook Mirae Technology while also developing the side-scrolling survival action game, Machine Instinct, as well as an unannounced dark fantasy action RPG. To learn more, visit: Vitalybulgarov.com and MachineInstinct.game

GW: Vitaly: can you describe your day-to-day responsibilities as a Principal Designer at Hankook Mirae Technology?

VB: Of course! But first I have to say that while I’m on staff at HMT, I’m currently taking a three month break from my duties to focus on my video-game projects, especially the new game. I felt this was necessary to make sure the foundation of the game is as best as it can be. After that, if I can still manage a part-time involvement with Hankook Mirae's projects, I'm hoping to do just that. I joined Hankook Mirae back in February 2014 and since then have generated numerous designs for the company with some of them still waiting to be prototyped. That, plus company’s tech team being busy with researching some of the core technologies, allowed me to get a hiatus where I can work on my other long-time passion: videogames.

As a Principal Designer at Hankook Mirae I was granted a very lucky position to make a design impact on everything that the company does but with minimum management overhead. My day to day responsibilities would generally funnel into two project types which can also be tightly correlated with specific project stages and company’s short-term and long-term strategic goals. So I would constantly jump between the following groups of tasks:

1. “Blue-sky” also known as RND (Research and Development) is an early conceptual design session, where we explore ideas where “everything is possible”. This category of projects generally involves wild explorations around robotics and set out to spur discussions as well as inspire the engineers and designers on the team both in terms of function and aesthetics. The most interesting of those ideas still haven’t been presented to the public and are in the RND stages. I’d say this is my favorite and most autonomous part of the job as I get to explore a lot of really fun ideas and use any tools/software/workflow I want.

2. Industrialization. This entails the selection of concepts and working closely with the engineering and design teams to bring the chosen concepts to life. This is definitely the challenging part of the job where things need to be designed “to spec” using CAD modeling tools, making sure it all fits together cohesively from a technical standpoint, i.e., the parts have proper range of motion and it all can be manufactured cost-effectively. Robotic products are inherently complex with a lot of moving parts and there is a constant battle between what can be done and what we think could be if we just push the limits hard enough. It’s both inspiring and daunting and always keeps you on the edge of your seat, while also creating this natural habitat where you get to learn something new every day.

GW: What led you to also working as an indie video game developer and what led to the development of Machine Instinct?

VB: In 2016 and 2017, we were really busy with mostly robotics work, so I didn’t have a whole lot of time to start a big side project, but I wanted to find a way to get back into videogames in a role that’d be both fun for me as an artist, but also meaningful for me as a creative. Not to mention, I wanted a way to also learn new things on the engine side. Particularly, I wanted to learn Unreal Engine and node-based visual programming and be able to finish a working game prototype all by myself. I thought it’d be a good personal challenge but also a way to unplug/decompress from my daily work. I enjoy learning and went through a bunch of tutorials on UE4 on Epic Games’ official Youtube channel. I thought it’d be fun to make a dark and challenging sci-fi side-scroller survival game where the player has to defend the platform from waves of hostile robots in a tactical combat. At the time, I also played the game called Devil Daggers and really liked how unforgiving and challenging it was and how you were instantly thrown in the middle of deadly action. So, with that inspiration, along with some classic 90’s side-scrollers in mind, my goal was to make a game that can be played in short sessions where you’d try to beat your previous score based on how long you survived and “held the position” without having to poor dozens of hours into the game. The idea of controlling a mechanical dog that can transform into a robotic werewolf wasn’t there at first. When I studied the lessons on unreal engine I had to make a character to experiment with and since the Robodog from Black Phoenix was something I’d already done years back, I thought it’d be fun to actually use it for something. I went with the approach of using 2D rendered sprites for characters and 3D models for environment. Once I had the base sprite of the dog running around and shooting a plasma rifle attached to its body, I instantly felt that that was who the main character of the game should be. That is also when the basic story/setting of the game came to be as well. Later on, in order to bring some melee action into play, and also add a break for controlling a quadruped character all the time, I thought it’d be pretty sweet to be able to use a power-up that transforms the robodog into a menacing bipedal robot and it all unraveled from there. One of the fun and rewarding parts about being an indie game developer is being able to experiment with faster turnarounds and take creative risks. That exploration and the fact that you get to do almost everything on a project is very meaningful. Once the prototype was complete, I asked two of my friends: a rigger/animator and a programmer to help me take the project quality to a more acceptable level (when I did the prototype, both my animations and programming were really bad). While the rigging/animation and proper programming work was being done, I could focus more on gameplay and finalizing content. Currently, all the art content for Machine Instinct is done and the game is being polished and fine-tuned on the programming side of things. Initially, the plan was to release it in late March or April, but it might get delayed due to extra polish it might need on the gameplay side of things and me being busy with another project.

GW: What are your current goals and current challenges for the ambitious, unannounced video game title that you’re working on?

VB: Even though most of my work is futuristic design, the Medieval, dark-fantasy setting has always felt like a “home” to me. It’s something I’ve loved since I was a kid, and now as an adult it’s a form of reflection on the past of humanity—its myths and its hidden unknown side. Needless to say, I’m very happy to finally be able to work on such a project. After almost a year of pre-production, we just went into production phase of the project and the first important goal is to establish a proper foundation for all the new people joining the team. We’re a small indie team, many of us still having either full-time day jobs or part-time freelance to support ourselves, but, we’re striving to make something unique and for the size of our team, something that hasn’t been done before. The challenges are definitely correlated with the small team, limited resources, and, of course, setting the bar high on both the visual side and gameplay side of things. I can’t say much more about the game itself yet, but we have made limited announcements to help us hire new team members. But please stay tuned for future updates!

GW: What have the latest versions of tools such as ZBrush brought to the table and how has your design process been influenced or changed?

VB: My daily work for the past few years has relied mostly on CAD modeling but I’ve started using a combination of CAD and ZBrush recently on the videogame project to generate designs and highpoly models of weapons and props which proved to be a very effective workflow. I’d make a base of the model in Moi3D and then detail it in ZBrush. Moi3d has an excellent Obj exporter that allows the user to control the density of the meshes. That way, the user can export sculpting-friendly meshes ready to be detailed inside ZBrush. I just finished the main character’s sword design using this method and currently working on a series of props and a few robotic designs also with that approach. I still rely mostly on standard sculpting tools though. Although with every new ZBrush version, there is always something new to add to my daily tool-set!

GW: What do you use for inspiration when creating futuristic designs?

VB: First and foremost, any functioning technology object (past or present) is a starting point of inspiration for any futuristic design. To me, it’s always inspiring to look at something functional and break it down: How is it built? How does it operate? What makes it useful? What can be improved? Now, the visual side of things and the aesthetics mostly comes from music. Music has been a reliable long time inspiration source for my design work and depending on what kind of work needs to be done I choose the music accordingly. I’ve been listening to a lot of experimental or unknown/underground niche subgenres of electronic music to get inspiration for futuristic designs. For the Dark Fantasy game work, I have been relying on dark ambient and heavy atmospheric black metal. One of the more recent discoveries for me was Rhythmic Noise and Power Noise. I enjoy the music that possesses both order and chaos. To me, that’s the zone where learning and evolution/innovation really happens. So, I try to take that thinking and apply it to my design work and take creative risks while still keeping part of the work grounded. I feel like listening to music that is both appealing but also challenging—forcing you to grow in some way—is a good booster for concept-art work in general. There is some kind of weird magical link between the audial and visual channels. When you just get inspired by something you see, the tendency is to either copy that or make an interpretation or iterative evolution of it. But when you hear music there is a chance that you’ll create something that is truly new or interesting and is not an interpretation of anybody else’s “literal” visual design. That being said though, I of course also get inspired by any good/interesting design work out there. There are plenty of great creative artists/designers on Pinterest and Instagram to get your daily dose of inspiration from.

GW: Out of all the clients you’ve worked for like Dreamworks and Blizzard Entertainment, is there a project that still stands out and resonates with you today? And why?

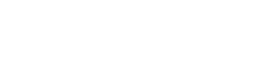

VB: I think designing Major’s cybernetic body for 2017 “Ghost In The Shell” film still stands out as a very special experience for me. As a huge fan of the GITS universe, it was a great honor and also a very meaningful project of which to take part. Designing the body from the ground up, (from the robotic skeleton; to muscle layers; to the skin layer; and everything in-between) was both a daunting and fun task. What made it personally memorable is how demanding it was from both the artistic and technical stand point. It seemed like a project that fully utilized everything I had learned over the decade prior to taking that job. The anatomical sculpting experience I’ve gathered during my character modeling years came in very handy when creating the skeleton and laying down the muscles, while the CAD design experience from working on industrial design projects helped me to build the skeleton using Moi3D. The final 3D design was composed of the skeleton modeled with Nurbs(Moi3D), muscles made with SUBD polymodeling (Softimage XSI), and the skin layer sculpted in Zbrush. It was perhaps one of the heaviest scene files I made for a film project. It was an absolute blast to see it being beautifully built by Weta Workshop and then see it on a big screen in a movie theater.

GW: Are there uncommon subjects you’ve studied or out-of-the-box advise you could share with aspiring artists?

VB: It’s probably not so uncommon anymore, but still one of the first non-art related subjects that helped me immensely with my art was practicing rigorous time management and studying personal efficiency. At some point in my career, reading the books on time management, planning, and just overall “personal growth” was the key factor in transforming my productivity. Such works as “Compound Effect,” and “Eat That Frog,” as well as “Mastery,” and “Deep Work,” provided a very practical knowledge, as well as supplied the right kind of work philosophy and professional mindset that have become hugely helpful in both studying and completing real world projects. One of the essential skills I was inspired to develop after reading those books was a habitual break down of any task into a sequence of smaller tasks. That didn’t just help me get things done faster, but it also gave me a better structure to analyze where my weak spots were and which fundamentals I should focus on and what to improve.

One of the things I use constantly to stay on track is timer. Once I break down the project/task into “easy digestable chunks” with actionable steps, I then set a “micro-deadline” using a timer to get each step done. The goal here is mobilize my attention to a task at hand and to prevent distraction and mind-slips into any irrelevant tasks and thoughts. In fact, I’m using one right now to answer the questions to this interview. I’ve been seeing more and more artists using this approach over the last years too, and one of the questions I get asked often is what to do when you’re overwhelmed with multitasking, or if your work is made up of new kind of tasks (that you can’t estimate the amount of time they’ll take to complete because it’s something you haven’t done yet before). For that, my advice is as follows: instead of setting a timer, set a stopwatch, and preferably write down the time you started on that task in your timelog/journal. That way as the time passes you know how much that task is taking. Doing so brings two important benefits: 1. Learning how to plan/budget for new tasks for future instances of those tasks. And 2. Giving you a reference point of understanding whether a certain task or an approach you took to accomplish certain goal becomes a time sink and whether you need to adjust future plans/goals or abandon/change the approach.

GW: What was your experience collaborating with Gnomon Workshop like?

VB: My first ever experience working with Gnomon Workshop was back in 2008 when I made a DVD class on Character design/modeling. GW team helped me a lot with the technical side of that and basically did whatever they could to make sure I stay focused on the class itself. Since then, I had the pleasure to collaborate with Gnomon regarding a few more master-classes, events, etc., and I can only say positive things about my experience so far.

GW: How did the design of libraries using reusable 3D parts to help concept artists, VFX artists, and rapid prototyping enthusiasts come about?

VB: The first time I had an idea to design reusable 3D parts was around 2007-2008. At first, I only wanted to make my own small library of bolts and simple hard-surface details for my own use on a game project I was working on as a freelancer. But I never thought about making complex custom design parts at the time. Sometime later, I saw ILM’s “Making of” videos regarding the VFX for Transformers. They talked about building a library of reusable realistic highly detailed 3d models of internal automotive parts such as engine parts, transmission, crankshaft, pistons, etc. That’s when I first saw the potential and a certain yet unoccupied niche (which was the models that weren’t copies of specific real world parts, but something more in line with never before seen futuristic conceptual design that would be really appealing and helpful for sci-fi works). What crystallized this idea was my experience of working on “Starcraft 2: Heart Of The Swarm” Cinematic intro. The Art Director of the project, Jonathan Berube, had an idea to use real world tank details on a sci-fi Terran siege tank. So, I made a small library of those and tested it on a real project for the first time. That inspired me to try it on the bigger scale with more complex details. I took some time off and built a much bigger library with more complex unique parts to speed up the design process even further and tested them on a “10 Days Of Mech” design exercise, which later became the foundation of design language/style for “Black Phoenix Project” as well as “Machine Instinct” side-scrolling game.

GW: SO much heartfelt thanks to you, Vitaly Bulgarov! Your insight is most appreciated; thank you for collaborating.

VB: Thank you so much for the great questions, Genese Davis, and for the opportunity to share my thoughts and talk about my experience!

| Check out Robotic 3D Design for Entertainment with Vitaly Bulgarov |