Madeleine Scott-Spencer

Madeleine Scott-Spencer has used ZBrush extensively for over ten years as a Visual Effects artist and has worked with Weta, Double Negative, Pixologic, Gentle Giant Studios, Activision, and Hasbro. She is an in-demand instructor for The Gnomon Workshop and has been featured in various publications such as 3D World Magazine. As a designer at Weta Workshop, Madeleine Scott-Spencer worked on the Hobbit trilogy and went on to work on a variety of other films such as Rise of the Planet of the Apes and Wonder Woman. Scott-Spencer authored highly-regarded books such as ZBrush Character Creation: Advanced Digital Sculpting, ZBrush Creature Design, and ZBrush Digital Sculpting: Human Anatomy. She graduated from Savannah College of Art and Design and studied classical figurative sculpture at the Florence Academy of Art. To learn more, visit Madeleine Scott-Spencer’s ArtStation, LinkedIn, and Gnomon tutorials.

Madeleine Scott-Spencer has used ZBrush extensively for over ten years as a Visual Effects artist and has worked with Weta, Double Negative, Pixologic, Gentle Giant Studios, Activision, and Hasbro. She is an in-demand instructor for The Gnomon Workshop and has been featured in various publications such as 3D World Magazine. As a designer at Weta Workshop, Madeleine Scott-Spencer worked on the Hobbit trilogy and went on to work on a variety of other films such as Rise of the Planet of the Apes and Wonder Woman. Scott-Spencer authored highly-regarded books such as ZBrush Character Creation: Advanced Digital Sculpting, ZBrush Creature Design, and ZBrush Digital Sculpting: Human Anatomy. She graduated from Savannah College of Art and Design and studied classical figurative sculpture at the Florence Academy of Art. To learn more, visit Madeleine Scott-Spencer’s ArtStation, LinkedIn, and Gnomon tutorials.

GW: You’ve worked both in traditional and digital sculpting for various professional projects. How do you view the two platforms and how did you make the transition from traditional sculpting to digital sculpting?

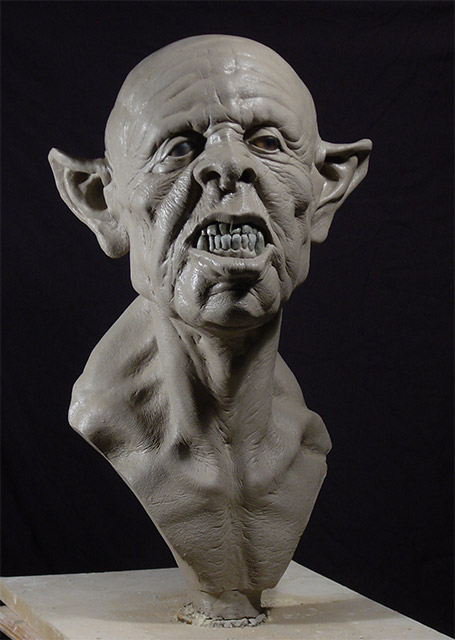

MSS: I came to clay early in my childhood. I grew up mask-making. Naturally, my first love became makeup effects. This discipline, where everything is rooted in painting, sculpting, chemistry and mold making and creating prosthetics, animatronics, creatures and characters, and so on, was where I learned my preliminary lessons in art and design. All the artists that I looked up to were in makeup effects. Rick Baker is a great example of a makeup effects award winner whose work in ZBrush is also stunning.

I love clay. I love touching the form and making the form with my hands, and digital sculpting is almost the halfway point between drawing and sculpting to me, because ultimately, it is existing in a two-dimensional plane and you are not touching the shapes as you’re making them. There’s something visceral and tactile about creating a zygomatic arch, or creating the folds of flesh and carving away and adding clay that you don’t have digitally, but everything that I learned in clay, and everything that I know about clay, comes into ZBrush and into that sculpting experience digitally. So, I am still pulling from all those same pools of information. It’s just a slightly different experience of executing it.

GW: How did you approach integrating or altering the habits and routines that developed from sculpting traditionally to sculpting digitally?

MSS: Making the leap—that leap into the tool that is existing on a screen and that you are interfacing with from a tablet. Knowing that it is still very immediate and still very much “at your fingertips,” but just existing in that slightly different space. With my traditional sculpting, I have to get up on the desk and see the top view then jump down and look at the bottom view. In ZBrush, I can simply turn the camera. And I don’t have to clean up. I can get up in the middle of the night and sculpt and go back to bed.

The responsiveness of digital tools compared to taking a little ball of clay and picking it up and putting it down and shaping it is a different experience of course, but it shares so much of the same territory that I can transfer my experience with clay, creating traditional props and monster parts, to the digital realm. It is not necessary for an artist to have experience in both: I know a lot of fantastic digital sculptors who have never touched clay and I know fantastic digital sculptors that started in clay.

GW: After your affinity for ZBrush developed, how did that evolve into authoring instructional books on the subject?

MSS: I come from a makeup effects background, so I wrote my first book imagining that I was teaching ZBrush to makeup effects artists. I knew a lot of artists in makeup effects who were looking to make the transition into digital, and it was ZBrush that offered almost the same tangible experience where you can literally just start painting and sculpting. I was excited to see how experienced artists who have sculpting and painting backgrounds translate their skills right into the program.

I had been thinking about wanting to write a ZBrush book when my colleague at Gnomon, Eric Keller, recommended me to his publisher to write the book. I was really overwhelmed but also thrilled to do it. So, I jumped in.

What really helped is that I had been teaching ZBrush at Gnomon already for years, so I already had a base outline to follow. From there, I thought about how I communicate the methodology behind this software—the logic behind it. Some people come to ZBrush confused by it, but there is a logic to why it is the way it is. I also had wonderful editors throughout my book’s publication process which really makes all the difference in the world. Without an editor hounding me about my deadlines I would have taken forever.

GW: ZBrush has so many pros. Are there any cons you’ve found? If so, how do you mitigate those and find solutions?

MSS: Generally, I do the majority of my work in ZBrush and Photoshop. There is now a plug-in that streamlines that process of going from ZBrush to Photoshop. So, the things that used to be tedious like rendering and exporting passes and processing them and compositing them in Photoshop could be a pain, but now that has been streamlined. If I am going into another program then it most likely to do something that I don’t think ZBrush has intentions to do. For example, I use Mari to do texture painting, but most of the time there is a way to do what I want to do in ZBrush. If the program is unwieldy in some area, then most likely the developers will work on a work-around.

GW: You have collaborated on blockbuster projects such as Pacific Rim 2, Wonder Woman, and The Hobbit Trilogy. How did you get your foot in the door to the movie industry, and how easy or difficult did you find the work on these films?

MSS: I decided to go to art school. I had found that there was a vocabulary that I didn’t have before getting a formal training, like for instance regarding color temperature and value. I respond well to classes. I love teaching, too, but I still take classes to this day. At first, I was going to school for animation but I ended up doing stop-motion and hand-drawn animation. My minor ended up being in drawing and I took a lot of concept design classes and I did sculpting on the side. Then ZBrush came out and it hooked me. I developed a demo reel and after I graduated I went to work for Gentle Giant in Burbank. Gentle Giant was a fantastic place to work that worked in polygons and pixels and clay and wax for collectibles and toys and fine art and models and textures for games and films. After working there for several years, I was invited to teach ZBrush by Richard Taylor which turned into an offer to move to New Zealand and work at Weta.

It was exciting to move overseas. There is that common worry that once you move you will be isolated and removed from everything that is going on in the industry but once you become immersed in your work, that worry ceases. Working on the Hobbit designing for Guillermo del Toro for a year was amazing, and then I worked for Peter Jackson who took over the film, and redesigning for Peter was also a great experience. From there, I continued working on all kinds of different films, and even to this day, after living overseas for quite a while, I continue to be surprised that I am the one with the accent versus the other way around.

GW: Is there a difference between the pressure working in the US versus working in New Zealand?

MSS: It is actually very similar because in concept design, I find that we are not crunching in the same way that happens in production. We are ideating—getting idea out—so the stress is different. Our stress is more “the directors are not responding to this,” or, “I’m not hitting the notes that they want,” or, “no one is getting excited by this particular design.” That is the type of stress. You seem to only be as good as whatever you do that day. You can have a wonderful day where you do something that is really exciting for the directors, and then the next day they change their minds, or nothing you’re doing seems to really shine.

GW: You have taught at The Gnomon Workshop sharing with audiences the intricacies of your work. Is there an experience that stands out to you about Gnomon that you can share?

MSS: Ryan Kingslien recommended me to teach at Gnomon. After chatting with Alex Alvarez who vetted and approved me to teach, I fell in love with teaching. I have so many wonderful memories of different students and hearing back from students who took my classes at Gnomon. One of those students who took my classes was eighteen years old at the time and years later pinged me with news that he had become a supervisor at ILM. It makes me so happy to see these students go forth and do what they love and intend to do. I had another student, an online student, who was one of the most driven students ever. She was incredible. Her dedication, her ambition… After two years of taking my Introduction to ZBrush class she was working with me at Weta. Seeing people like her, devouring information and turning it into their dreams is exciting. I love that so much. I don’t think you know anything truly until you can communicate it to someone else—teach it to someone else. I love teaching and try to teach at least one course every semester. I have been teaching consistently at Gnomon for eleven years now. I taught in Los Angeles when I was living there and I continue to teach online classes. In every class I always share with my students that out of everywhere I have gotten to work and everything that I have done, teaching my classes and the books I’ve authored are the most precious to me.

GW: Human skeletal anatomy is one of your go-to guides when designing multiple characters. Can you describe how you garnered such extensive experience in the subject?

MSS: I’ve been studying anatomy since college and I’ve always enjoyed buying anatomy books and taking anatomical classes in school. I studied with Paul Hudson, an incredibly talented anatomist, at the Florence Academy of Art. From a theoretical perspective, I would try and dissect something from a book by looking at the front side and three-quarter side, but then I had the opportunity to do fifty hours of cadaver lab research. That experience of touching the form, cutting away and peeling back, that tactile experience was invaluable. Seeing the shape and the size and the relative thickness of the muscles and understanding how they relate to each other in life rather than in a book was hugely beneficial. You do have to parse the fact that it is a person in front of you, and I had quite a few moments of trying to justify that I was there for art, not as a medical student, and that that was okay. Medical students are able to process this adjustment with their peers, but I was there alone in a room with twenty bodies doing my self-guided cadaver dissection using Grant’s dissector. No one to bounce anything off of. It was just me. And I found myself sitting there wrestling with the idea that this was taboo, and that I was not supposed to be intruding on this body—this person! Then I remembered that it was okay and that I was allowed to be there—that this was science and art. It was really heavy and intense but also a wonderful experience. I encourage my students to seek this out because we as lay people have a lot of taboo built up for cadaver labs that does not actually exist in cadaver labs. A lot of times the lab monitors will be really taken with the idea of an artist wanting to learn and observe and do research and will therefore allow access. It is an unparalleled experience and the lessons I learned in the lab I use every day.

GW: What are your thoughts on future technology breakthroughs in digital sculpting, or for the CG industry as a whole?

MSS: There is a lot of talk around haptic technology. Haptic devices like the sculpting gloves that utilize force feedback, so when you touch the digital clay you feel the clay. At Gentle Giant I was able to dabble in some of this and it does bring that tactile aspect, that extra level where the artist can feel the ridge that the edge of the thumbnail makes. Thinking about this force feedback virtual reality interface with our sculpting then brings us back to the first question of this interview—using our physicality to influence the shapes that we are making. All of that is exciting. It is probable still a long way off but it is still something that people are talking seriously about and definitely putting a lot of time and research into.

GW: You are a creature designer to boot! Are there steps in a creature designer’s workflow that should not be skipped? Have you ever found yourself stuck and realized going back to primary shapes or gathering more reference photos was needed?

MSS: Ironically, it is the routine that I have to try and break away from. In my design classes I speak about how we have safety shapes that we go back to and we lean on, or what intrinsically becomes our style. I find myself leaning on my style and I try diligently to break that habit. Because I am aware that I follow routines, I can focus on bringing a unique angle and new perspective so that the director, for example, can be inspired by that new collection of beautiful shapes.

A lot of artist might use fractal thumb nail generators, Rorschach ink blots, or random patterns where one tries to find the shapes and creatures in there to break away from their conscience mind and get into that subconscious muck and find something really cool down there instead of the superficial layer in creatures we have seen over all our lifetimes.

GW: Lastly, are there any favorite art books or styles that you constantly refer to and that still influence your work today?

MSS: I love the art and the work of the 1970s and 80s creature and character designers and artists, like Rob Bottin, Rick Baker, and Stan Winston, and designs like Pumpkinhead which is one of my favorite creature designs ever. I like that and looking at things that others may not be as aware of like natural history as a source of inspiration. Also, symbolist painters, like Carlos Schwabe and Gustave Moreau. It is this wonderful 19th century proto-surrealist dream world which I find really inspiring.

I try not to spend too much time looking at other digital artists’ work in terms of finding inspiration there. Don’t get me wrong, I am inspired by my peers, but I am very careful not to fall into these zeitgeist traps where everyone is doing the same type of thing. I worry about that so I try and stay balanced by looking at obscure and new sources of information. A vast vocabulary of shapes and ideas enables you to find just the right shape and idea you need.

GW: Thank you Madeleine Scott-Spencer for not only sharing your pro tips and tricks with us today, but for also sharing them on a continuous basis with students around the world. The approach and meticulous detail you invest into your work is inspiring to all. Cheers!