Eric Keller

Eric Keller is a skilled and accomplished CG artist and creator. He has been a professional CG artist since 1998 specializing in scientific visualization but he also works in the entertainment and commercial industries. Keller’s Hyper-Realistic Insect Design and various Maya tutorials for the Gnomon Workshop demonstrate one-of-a-kind methods, tips, and tricks that Keller has perfected. Keller’s students have been featured prominently on Artstation and have gone on to work for a plethora of industry giants. Eric Keller has written numerous books on Maya and ZBrush (Mastering Maya 2009, Mastering Maya 2011, 3 Editions of Introducing ZBrush, and two editions of Maya Visual Effects: The Innovator's Guide). He has lectured at ZBrush User Group meetings, and has given presentations at the ZBrush booth at SIGGRAPH. Below, Eric Keller discusses his key passions including how he is using CG to further scientific research and science education, and his future predictions not only for the dominate software emerging but also what he hopes artists and creators will bring to CG in the future. Keller’s latest personal project, Entomology Animated, focuses on the biology of insects and demonstrates an exuberant approach to CG, animation, and science.

Eric Keller is a skilled and accomplished CG artist and creator. He has been a professional CG artist since 1998 specializing in scientific visualization but he also works in the entertainment and commercial industries. Keller’s Hyper-Realistic Insect Design and various Maya tutorials for the Gnomon Workshop demonstrate one-of-a-kind methods, tips, and tricks that Keller has perfected. Keller’s students have been featured prominently on Artstation and have gone on to work for a plethora of industry giants. Eric Keller has written numerous books on Maya and ZBrush (Mastering Maya 2009, Mastering Maya 2011, 3 Editions of Introducing ZBrush, and two editions of Maya Visual Effects: The Innovator's Guide). He has lectured at ZBrush User Group meetings, and has given presentations at the ZBrush booth at SIGGRAPH. Below, Eric Keller discusses his key passions including how he is using CG to further scientific research and science education, and his future predictions not only for the dominate software emerging but also what he hopes artists and creators will bring to CG in the future. Keller’s latest personal project, Entomology Animated, focuses on the biology of insects and demonstrates an exuberant approach to CG, animation, and science.

GW: What inspired your entomological obsession?

EK: The short answer is "E O Wilson". The longer answer is that I had an epiphany. Around 2009, while working on a short CG movie for the Boston Museum of Science, I realized that insects have it all for a CG artist. They are both organic and hard-surface. Their exoskeletons are often finely detailed with vibrant colors, some are metallic, they are usually hairy, deliciously translucent, shiny, dull and everything in between. Endless varieties of surface properties to explore, and I love developing shaders to mimic these properties in my renders. Insects are also easy to rig and a joy to animate. Most importantly, they are the perfect subject to engage people in science because they are simultaneously alien and familiar.

Shortly after I had this epiphany my good friend Gael McGill who started a scientific visualization company in Cambridge MA (www.digizyme.com.) won a contract with Apple to help the famous biologist E O Wilson develop a digital biology textbook for the iPad. Gael hired me to be the lead 3D artist since we had worked on many jobs together before this, including the film for the Boston Museum of Science. I felt like it would be a good idea to read some of Ed Wilson's books before starting the job. He has written A LOT of books, mostly on ants, but also on ecology and philosophy. Wilson is most famous for his many discoveries related to ant sociobiology. His writing is so engaging and so captivating that it pretty much convinced me that insects desperately need their story to be told, and that computer animation is the best way to do this, and I'm the best person to do it! I had been doing cell and molecular biology animations for years, while these are interesting subjects for animations and they are always a fun challenge, molecular and cellular dynamics are not nearly as engaging to a general audience as insects. Unlike our buggy friends, molecules and cells don't have a face or eyes that you can stare into. We finished "Life on Earth" in 2014 but since then my interest in insects continued to grow and continues to inspire me like no other subject. I started hanging out at the Natural History Museum in LA and made friends with the entomologists there as well as others online. There definitely exists a kind of person that gets really excited about insect biology. I guess I've discovered, only in the past few years, that I am one of those people.

GW: The intricate detail you obtain in your hyperrealism work is phenomenal. What helps you achieve that level of success?

EK: A microscope! I have one beside my Cintiq and I use it constantly when exploring insect shapes in ZBrush. Also, I try and practice macro photography whenever I get the chance. I have participated in a number of macro photography workshops run by a group called "Bugshot" that is run by scientist-artists who all have years of experience in the field and in the lab. I've gone to one of these workshops in Carmel, California, one in Austin, Texas, and this spring, I'll be attending one in Gorongosa Mozambique. What I love most about studying insects, whether it’s through the lens of a camera or microscope, is examining the amazing shape language and detail of their exoskeletons and seeing how faithfully I can sculpt them in 3D. I also have a number of experts in the scientific community that I can turn to for critiques. I've become friends with Brian Brown, Emily Hartop, and Lisa Gonzales at the Los Angeles Natural History Museum as well as Myrmecologists (ant specialists) Terry McGlynn, Seth Burgess, and Alex Wild. Talking to an expert entomologist the best way to learn how much I don't know. That weird little blob at the base of the abdomen may look like nothing to me, but, to a trained eye, it could be the difference between two entirely different species. I'm currently working on a model of a type of beetle that folds up like a Transformer. An Italian scientist named Alberto Ballerio sent me a few specimens (dead of course) to examine under the microscope. I'm still trying to get it correct, it is one of the hardest models I've ever done because of the fact that it is a complex beetle that has to curl up into a ball and each piece fits together perfectly. There is a version on my website at www.bloopatone.com in my portfolio but it is still a work in progress.

GW: How difficult is it to obtain real-life insects for reference?

EK: Not hard at all! Which also adds to the appeal of insects. I had a Malaise trap (a special trap designed for collecting flying insects) set up in my backyard as part of the LA Natural History Museum's Bioscan project. The museum let me keep it after the survey project was done. I used it to collect bugs for several months so I now have a disturbing number of bottles full of dead bugs soaking in alcohol on my bookshelf, next to my small library of books on insect biology. I haven't even scratched the surface of what's in my collection yet. And of course, I can always just wander into my backyard and observe them up close and in person. The downside of living in Los Angeles is that bugs aren't nearly as abundant as they are on the east coast. For some reason, my wife, Zoe, does not see this as a "downside" of living in LA.

GW: When restricted to gathering reference photos, what details do you focus on finding? Light, angle, atmosphere, positioning, lens type?

EK: The process of gathering reference through practicing photography is actually the best way to learn about insects. For one thing, living insects look very different than dead ones. I started out practicing photography by taking pictures of dead bugs that I bought from shops and bug-fairs, but I quickly learned that they just don't look the same. Seeing a bug move in its natural environment reveals much more about their anatomy; their coloring is different, their eyes shine, and their limbs glow in the sunlight. Their movement reveals the function of their limbs in four dimensions. Dead bugs tend to be shriveled and desiccated which can affect their proportions. Photography is great because it forces you to get away from the computer screen and you get a more holistic appreciation for how the insect is just one small part of the ecosystem. But the greatest thing about photography is that I can practice composition in real time. When I take a picture, I concentrate first and foremost on how the subject is positioned in the frame - not easy when they move so quickly or when a gust shows up right before I snap the photo. Then, when I'm setting up a CG insect model for a render in Maya, I think about the frame just like when I'm trying to take a photo of the real thing in the forest or in my backyard.

Lighting is my second crucial concern after composition. With photography, lighting is the aspect I'm working hardest to master. Because insects move so quickly (well some of them) the shutter speed must be very fast to reduce motion blur. This means you generally need flash in order to compensate for the reduced light reaching the sensor. But getting a pretty picture without the glare of the flash requires a lot of practice and specialized equipment like macro lenses and diffusers. When I set up my lights in a virtual environment I try and mimic this, with an HDRI creating most of the environmental light and then a few large bright area lights positioned like the camera flash. The best part about insect photography is that even if the bug flies out of frame before you can snap the image, at the very least you usually get a nice picture of a flower. Sadly, I have a lot of pictures of flowers on my Hard Drive, but the upside is that I can use these images as backdrops in my CG renders.

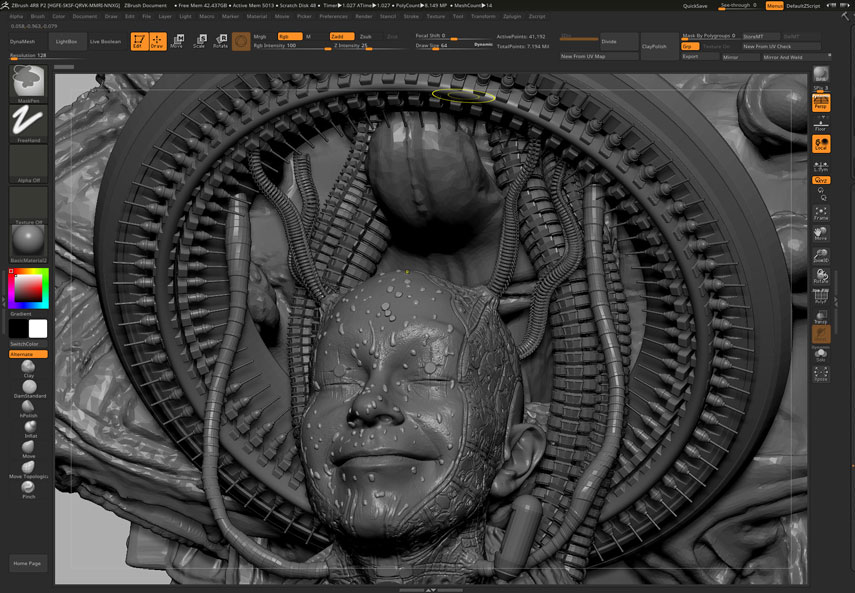

GW: How did your affinity for ZBrush and Maya develop? Are there strengths and weaknesses you’ve found in each?

EK: ZBrush and Maya are like members of my family. Which means I have to love them both even when they drive me nuts. ZBrush is the crazy uncle that can do the most amazing things while simultaneously making no sense at all. It takes a lot of practice and a few disasters to learn how best to work ZBrush into a production environment where things have a tendency to break and fall apart right as the deadlines show up at your door. It has gotten much better though, ZBrush 4R8 is a lot easier to use in production than the versions I was using 10 years ago.

Maya is my workhorse. It does some things extremely well, such as animation, rigging, and modelling. However, it seems to lag behind other applications when it comes to lighting and rendering which is why I depend on plug-ins such as Otoy's Octane. Houdini has pretty much taken over the industry as the go-to dynamics package. I used to do much more dynamics than I do now, and back then I did all of it in Maya. If I were to go back to doing dynamics work I would probably dive deeper into learning Houdini. Maya is ubiquitous in the industry, every studio I have ever worked in has had Maya at the center of the pipeline.

I started using Maya in 1998, around the time many of my Gnomon students were toddlers. I had used Lightwave which I liked and a few other ancient programs that have long since gone extinct, but the animation tools in Maya made it a better choice for the types of complex scientific animations I was doing at the time And I had the benefit of working at an organization that could afford the license. In 1998, a Maya license was over twelve grand!

I had heard of Zbrush early on when it was more of a whacky 2.5 dimensional illustration tool. When "The Return of the King" came out a few years after ZBrush debuted I read about how it was used to create the King of the Dead character and I decided immediately that I needed to learn ZBrush. I use it mostly as part of a production pipeline so everything from dividing cells, to alien creatures, to the rocks in the Power Rangers movie titles. In addition to sculpting objects, I frequently use it to create complex blend shape sequences for scientific animation.

GW: You’ve worked as a CG artist specializing in scientific visualization for renowned places of education, including Harvard, as well as for medical institutions. Is this how your passion for teaching began?

EK: I come from a family of teachers. Both my parents taught chemistry. I also have a brother who is a very well-known yoga instructor, and another brother who teaches audio engineering and live sound recording. My twin brother has just started teaching ZBrush at the Baltimore Academy of Illustration. Teaching is my favorite way to learn and it comes very natural. I guess I feel like I don't understand something until I can explain it to someone else. I studied music in college which meant I spent five to seven hours a day alone in a little room practicing scales and learning Bach and trying to learn jazz. The best experiences I had in college were the one-on-one lessons with my music teachers, many of whom are still the best friends I have in the world. After college I started in computer graphics creating animations for scientists who were either trying to illustrate research for other scientists or teaching the public fundamental concepts in biology. So again, I was surrounded by teachers and students. It’s a happy place for me. I love learning and teaching is a great way to learn.

Gael McGill brought me in as a guest lecturer at Harvard Medical School a couple times and I hope to do it again. It’s really exciting but also really intimidating. Most scientists and students are really cool and fun to talk to but they are also crazy-smart. Some of the questions they ask about stuff like simulating viral mechanics in Maya I have to refer over to Gael.

GW: How did you break into the movie/commercial industry as well?

EK: When moving from Washington DC to Los Angeles, I knew only one person in the industry and only through online contact—I had never met him personally. I tried sending out demo reels and resumes to a number of studios big and small. At that time, I had already been a CG professional for about seven years, yet I got no response from anyone. Nothing at all, total silence. It was as if I’d mailed these studios a bag of wet socks. So, I asked my one friend in LA at the time (Dariush Derakshani) if he could help me find work. He got me a job doing movie title work at Yu and Company. I worked there on a variety of projects for a year or so. Form there I expanded my network of friends and picked up more work at other studios including Prologue, Imaginary Forces, and Filmograph. Those studios do mostly Motion Graphics for Movies, TV, and a lot of commercials. I've done some sports packages as well. I never want to do another sports package again unless bug collecting becomes a sport. Transitioning from Motion Graphics into doing movie related stuff is difficult only because those two worlds are fairly separate and VFX work seems to come and go in waves—it’s very seasonal. I'm much more comfortable with VFX work than motion graphics. My connections with Gnomon have helped me get the VFX movie work that I have done. Really it comes down to the people you know and your reputation. Most jobs come about because someone somewhere said, "oh yeah, hire that person, I worked with them before.” Or, “I went to school with that person, they are great and easy to work with and they get the job done." Companies are nervous about hiring someone based solely on a portfolio. This is because budgets are tight and deadlines are short. Bringing in the wrong person, even someone with a stellar portfolio, can be a disaster if that person is hard to work with. For this reason, it is extremely important to build up a network of friends in the industry who know you and can vouch for you. That is how you get the best jobs. This is also why students from Gnomon get great jobs, they have a school with a great reputation vouching for them. That is extremely important to studios. People frequently ask me if a Gnomon graduate is a hard worker. I always say, "if they survived Gnomon then you know they are a hard worker."

GW: You collaborated on 10 Cloverfield Lane and Cloverfield Paradox. How easy or difficult did you find the work on these projects?

EK: I spent six months in 2015 working at Bad Robot. I was hired, thanks to a kind word from Nathaniel Morgan who took my ZBrush class at Gnomon, to work on sculpting and texturing the big monster in the spaceship at the end of 10 Cloverfield Lane (spoiler alert: there's a big monster in the spaceship at the end of the film). It was a lot of hours and some stress but overall every second at Bad Robot was pure joy. I don't remember the stress, I remember the fun parts: the friends I made, and the food. The Cloverfield monster sculpt was so much fun because I pulled out every ZBrush trick I had in my bag and a lot of the detail work was inspired by the hours I spent studying bugs under the microscope. They also gave me a lot of creative leeway. I did not follow a specific piece of concept art, just rough sketches and a verbal description. The initial model they gave me to start with looked a bit like Pac-Man with fangs since it was just a rough block in. So, I had to take that Pac-Man and turn it into this giant nightmare mouth. The best part of the production was when JJ Abrams came up to my workstation and inspected the model (yes, he knows his way around ZBrush!). He was surrounded by a big group of people, and after looking at it he gave the thumbs up and said "perfect". That was a great day for me. I also got to work on Star Trek Beyond while at Bad Robot—specifically the robot henchmen and some of the underground environments. I'm an unapologetic Trekkie so that was a huge thrill for me. I even got to model a bug for Star Trek but it only appears on the screen for a fraction of a second when it crawls out of a bag.

I worked for just a couple weeks on Cloverfield Paradox, very early in production when it was known just as "God Particle," building a model of the Helios station for Josh Viers who did the concept work. He was great to work with and an amazing talent. I also did some early animatics in Maya for the production but after the work on Star Trek ended they moved the production of Cloverfield Paradox/God Particle to Paramount. I moved on to other projects at Filmograph and other studios. The cool thing about working with Josh Viers is that I had a great time playing with hard surface models trying to translate his ideas from 2D photoshop paint over to 3D elements and back and forth. Modeling for a great concept artist is a lot of fun where you really get to push your skills into new areas. Everyone should check out Josh Viers' work.

GW: Were there any Gnomon Workshop tutorials that helped you forge your career?

EK: I started watching Gnomon videos back in 1999! Back when they were VHS tapes that you got in a big box in the mail. I called them "nerd tapes" and I used to do a little dance whenever the nerd-tapes arrived at my door. My wife Zoe can verify this, she has seen the dances. I had the whole VHS collection when it was just Alex and Darren and I watched them religiously. I think at one point I mounted a VHS player and a TV on an exercise bike so that I could watch while attempting a workout. Then Gnomon switched to DVDs and suddenly there were all of these other teachers like Meats Mier, Jeremy Engleman, and John Brown. John Brown's sculpting DVDs were the most significant—they changed everything for me. John's teaching approach was very similar to the approach of my music professors in college and that resonated with me. There is a real depth to his teaching but it’s also practical. Right before I encountered John's DVDs I was taking a sculpture class at an art school in DC and all they did was have a nude model stand at the center of the room and they said "sculpt!". Needless to say, I sucked at that class. But then I got John's DVDs and he had this pragmatic approach to sculpture that went from wire armature to finished product. My soon-to-be wife and I were living in Washington DC, and we were kind of getting tired of the East Coast scene (DC is not a very creative town). I remember saying out loud, "can we just move to California so I can take this guy's sculpture class?" She said, "yes, but we should probably get married first." So we did. We packed up our dogs and drove across country. I took John's class and we have become good friends since. I never managed to master sculpting in clay but everything I learned from John has influenced the way I work in ZBrush and Maya.

Of course, Alex Alvarez also had a huge impact on the way I teach Maya. I started out learning from his Intro to Maya videos. Years later they asked me to record the Gnomon videos for Maya 2014, 16, and 17 and I just finished recording a Gnomon Workshop series on UV texturing. It has been an honor to update the same series of Maya videos I watched when I got started. Pretty much any success I have as a digital artist I owe to the Gnomon Workshop and the Gnomon School of Visual Effects.

GW: You currently teach at Otoy educating users on the Octane engine. What stands out to you about Octane?

EK: Octane is very fast and physically accurate. It’s great for look development as you get a sense very quickly of how lights and material will look in the scene and they are easy to update while rendering. I love working with VDB files in Octane for Maya. The VDB format is a generic cross platform file format for volumetric data so I can add clouds and smoke and fore to the scene very quickly and easily and it looks great. I created a series of videos on the Octane integration into Unity which is really interesting. I think there are some interesting possibilities for using GPU accelerated physically based ultra-real rendering in a game editor such as Unity. The company has some big things in store for Octane in the near future and a bigger vision for how it can be used my more and more artists in the future. I recommend watching some of Jules Urbach's presentations on YouTube to get an idea of his vision of the future of rendering. It is pretty cool stuff.

GW: Does any other software stand out to you not yet mentioned that students and aspiring creators should consider?

EK: Substance Designer and Painter are so good it makes me angry! I honestly feel like younger artists can’t appreciate how hard texturing models used to be before we had these fantastic tools. I've had a few projects recently where I got great looking textures on my models so quickly I felt like I was finished just as I was starting to get my texturing groove on! I also really love working in Marmoset and Unreal, although I have much to learn in those programs. Real-time game engine technology is already taking over the industry beyond games. Unreal, Unity, Marmoset, Substance are all programs that students should embrace right away so that they can be prepared for the future. Because it is getting easier to create real-time renders that look amazing, I think within ten years software rendering as we know it will be dead and I will be the first in-line to dance on its grave. I love the Marmoset and I'm currently exploring it as a tool for scientific illustration. When I model an insect, I can send a link to that model in the viewer to a scientist who can then easily inspect the model in 3D in a web browser and then give me notes. It also has great potential for embedding into web pages for students who are studying biology.

GW: Do you have any hopes/dreams for future breakthroughs in the CG industry? Or do you foresee any interesting changes coming to the CG industry?

EK: The most important development I'd like to see in the CG industry is a shift to creating better content. CG is still mostly a shiny thing that we dangle before our collective eyes. It captivates our attention but there's not much beyond it. I'd like to see CG become more of a useful tool for communication and less of a distraction. Sci-fi and fantasy is great but it is so dominant now and its becoming like an addictive cultural junk food. I love French fries, don't get me wrong, but I feel like as a culture we've been gorging on French fries for the past 20 years with no end in sight and CG is the deep fat fryer that is currently enabling our addiction. There is a lot of important things going on in the world, big changes that are on the horizon from artificial intelligence, to climate change, to genetic manipulation, to space travel, to automation, and on and on. And it’s all happening at once. Computer graphics could be used as a tool to help us get a grip on the fact the world we are comfortable with right now is probably not going to be around much longer. But CG is like any other tool: it has great benefits but also some pretty dangerous downsides. When CG people and places are indistinguishable from real people and real places, it will become much harder to know what is really happening in the world and that makes me very nervous.

With regards to the future for individual artists, it is much easier to create stunning CG these days. In one afternoon, an artist can produce what it used to take a small studio to do in a month and that is only going to accelerate. CG tools driven by Artificial Intelligence are already available from de-noisers to texture generators to character animation tools. This means we'll have such an abundance of CG created reality, surrounding us all the time, that people will no longer be satisfied with looking at just images of spaceships, orcs, fabulous babes, and robots. And for this reason, I think that CG artists will have to start focusing more on making their skills and their tools more useful to society as a whole. In a few years, CG will be less technical—we'll be more like interior decorators, and less like technical artists. You can already build an ultra-real forest using Speedtree and Quixel's Megascans without the need to adjust a single polygon and there are many tools out there that allow non-modelers to kitbash some pretty impressive stuff. But this could all be a good thing because it forces us to work on a higher level. We can move from laboring over a leaf or a bush and work harder on the story that takes place around that leaf or bush.

In terms of technological development, I think Virtual Reality has yet to deliver on its potential but that doesn't mean it won't eventually. We are still in a place where putting on a VR helmet is a novelty and many people see it as a nuisance. For VR to become viable, it must get past the reluctance most people have to putting on a helmet. There's a reason Netflix and HBO dominate and it has more to do with chilling on a comfy couch than many VR developers appreciate. So, I think the shift is going towards Augmented Reality which lags behind VR in terms of quality but could help overcome the helmet hurdle as it doesn't cut off the user from their environment.

If VR or AR go mainstream it will be because of real time rendering. That could mean better GPU driven renderes like Octane or better game engines or a combination, but either way, real-time is the future. Jules Urbach, the founder of Otoy, has stated many times that he wants to create the Holodeck from Star Trek and if you look at some of the demos he's shown on line you can see that he is getting closer every day as are many other developers. That's where we are headed.

GW: What advice do you have for students preparing for the CG world?

EK: Learn your tools very well, learn how to adapt, and don't go in thinking that the specific job you get when you’re out of school now, will be the same job in five or ten years. Sometime soon, there will be no full-time texture artist position, or full time hard surface modeler, or full time lighter. Don't tie your career to a single skill or a single software package. Build networks of good people you like to work with and socialize with them frequently. Be very, very careful about "dissing" your fellow artists. It might feel really good to bad-mouth someone's work but you never know, that same person could be the person who decides whether or not you get hired at some point down the road. Respect the hard work of your peers, always be professional and have humility. It’s great to be proud of your work and you should be, but don't get a swelled head about it. Understand how to give and take criticism respectfully. Never, ever, ever walk out on a job no matter how hard it gets. If you leave someone else holding the bag the night before a big deadline, they will never forget that. I've seen a few people freak out and bail on a job at the worst possible time, like at 3:00am the night before a project is due. That is just about the dumbest thing you can ever do. If you find yourself in a truly abusive situation then seek help from someone but don't just walk out on your fellow artists.

GW: You are an expert multitasker—amidst all that you do, you also teach at Gnomon simultaneously. Which topics do your courses focus on?

EK: The guiding principal of the Creature Sculpting course I teach is to encourage students to develop good ideas and work that into the sculpt. Technical skill with ZBrush is not hard to achieve, it just takes practice. The real art is having a good idea and realizing it through the software. I took a class with Neville Page a few years ago, he is one of my favorite concept artists. He would always say that he does not hire the artists based on their technical skill, rather he hires the artists with the best ideas. It’s not as difficult as it used to be to create an impressive, detailed model, in fact that is rather common. It is much harder to convey an idea that the “beastie” you've just modeled has a place in the story, a relationship with not just the environment but also the characters, and most importantly, with the viewer. So, the assignments in the class are designed to get the students to work on their ideas, I don't let them model another artist's concept art. To start the class, I give weekly thirty minute warm up challenges and then we spend the rest of the time developing and critiquing their master project which they work on over the course of the ten-week semester. I also require them to figure out how to present their work at the end. My thinking is that they need to feel like the class is a simulation of a studio and it is their job to convince the art director that their idea is the one that should be in the movie or the game. It doesn’t matter if they do a turntable or a paint over or a Marmoset model, as long as it knocks my socks off as well as demonstrates an understanding of how to sculpt in ZBrush.

GW: Are there annual events or conferences you’ve attended that you’d also recommend to others?

EK: I usually go to SIGGRAPH. I missed the last two ZBrush Summits because of travel, but I hope to attend the next one. I taught a workshop at one of the ZBrusgh Summits a couple years ago which was a lot of fun. I went to the Austin Unity conference (Unite) this past year, that was pretty cool. I'm hoping to go the LA VR conference this year in May. GDC ,E3, and CES are all really big, hoping to attend one of those soon.

GW: In your downtime, have there been any favorite video games you’ve played lately?

EK: I'm not a heavy gamer by any means. I play usually about twenty minutes a day just to unwind when I get home from work (and before I start doing more work). I play Star Wars Battlefront 2 mostly because that is the game I dreamed of playing when I was growing up. I also occasionally play Rocksmith. It’s a bit cheesy but it’s not a bad way to keep up my guitar chops. You plug your guitar into the Playstation and it monitors your progress, shows your mistakes, and has great tools for learning how to play specific licks. The graphics are a bit goofy and I wish they had a broader selection of musical styles. There is an indie game about ants called "Empire of the Undergrowth" I want to play, just haven't found the time. The guy who developed it spent time researching ants which I have to respect.

GW: Are there any movies or documentaries that you return to over and over that are rich in resources or inspiration?

EK: One of my favorites, which is available on You Tube, is "Ants: Nature's Secret Power". It has some really goofy music and dead pan narration and it stars Bert Holdobbler who is one of the world's leading ant researchers. I love the Planet Earth and Blue Planet series and Microcosmos is a classic. The Nova special "Lord of the Ants" (yes, that's an ant-pun) is a great retrospective of E O Wilson's career, narrated by his good friend, Harrison Ford!

On weekends, sometimes I watch a double feature of "The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou" and "The Big Lebowski". I've seen "The Big Lebowski" probably a hundred times. I think that movie has a strange appeal to type-A workaholics. I think obsessive types all fantasize about just letting go and becoming complete slackers—our "inner-Dude". Quite a few of my friends are big fans of that movie and all of them are workaholics.

GW: You've released a series called Entomology Animated. How did that come about?

EK: That is a labor of love that I came up with after I finished work on E.O. Wilson's Life on Earth. I was inspired by a book called "For Love of Insects" by Thomas Eisner that details the chemical weapons used by insects and arachnids. Each chapter of that book seems like a script for an awesome movie. I wanted to create something that teachers could use, for free, all over the world to inspire a love of insects and biology in their students. I want to capture the spirit of Eisner's book as well as E O Wilson's work and the many Biology textbooks that surround my workstation at home. So far, I have created an animation that describes the stinging mechanism of the Red Imported Fire Ant (Solenopsis invicta) and the amazing explosive defense of Bombardier beetles. For the beetle, I created a fake video game using the Unreal Engine. If I ever have the time and money I would love to turn that into an actual game. Currently, I am developing a short series on how insect vision works.

Insects and arachnids provide a front row seat in the story of evolution of life on Earth. That to me is the most compelling story ever. And there are literally hundreds of thousands of stories to tell and mysteries to explore which is what natural history is all about. I wish I could release more animations quicker but I usually have ten different competing jobs going on at once, as well as a regular job and a couple dogs to feed, so I squeeze episodes of Entomology Animated in whenever I can. I'm trying to use game engine, real-time rendering as a way to speed up production. I'm working with my friends, Andrew Schauer and Inna-Marie Strahznick, on developing a format that is more like a podcast. The past episodes on the ant and the beetle are a bit too long-winded for the internet, so we're trying a new approach which breaks the larger topic of insect vision down into shorter segments. I'd love to do a regular entomology-based show that would be some weird mix of the BBC's Planet Earth, Drunk History, and Mythbusters.

GW: Thank you so much Eric Keller for the fantastic interview and for your incredible work both outside and inside the classroom!

For more information, visit Eric Keller’s website, ArtStation, and Gnomon Workshop videos.

| Check out Introduction to Maya 2019 with Eric Keller |