Charles Hu

Figure painter and art instructor Charles Hu is an instructor for the Art Center College of Design and for the Gnomon School of Visual Effects in Hollywood. Charles Hu received his BA from the Art Center College of Design and began his career at the L.A. Academy of Figurative Arts. Hu’s robust portfolio includes numerous portrait paintings, character design for film, games, murals, and comic books, plus, his work has been exhibited at Wendt Gallery. His passion for teaching drive him toward higher and higher art quality and production.

GW: Charles, you’ve worked in traditional figure painting for various projects and you’ve mentioned that you are “traditional” to your core, plus, you love talking art. Can you describe more about what the foundation of artistry means to you?

CH: Figure drawing and painting has been the core of my art passion for so long. I met my mentor, Steve Huston, back in 1998, and Steve has a very impactful way of teaching. He does not focus on solely technique, because the art can become too superficial that way, and can tend to “copy’ the look of other drawings. Many new artists have challenges when trying to discover their own art-core. Steve Huston taught me that every artist needs to learn a critical art foundation that includes how to observe, how to measure, how to use geometric shapes to turn into perspective, and how to construct an image.

I feel very lucky that I was able to garner a great foundation, which, I credit Steve for, and that foundation has led to many other opportunities and benefits. For example, I’ve been able to do comics books, character design for film and game pitches, portrait paintings, designs for murals, and instructorship… And I always tell my students that with the right foundation, you can go into any of these avenues, and more, be it concept art, graphic design, product design, etc. It all boils down to the foundation that you build.

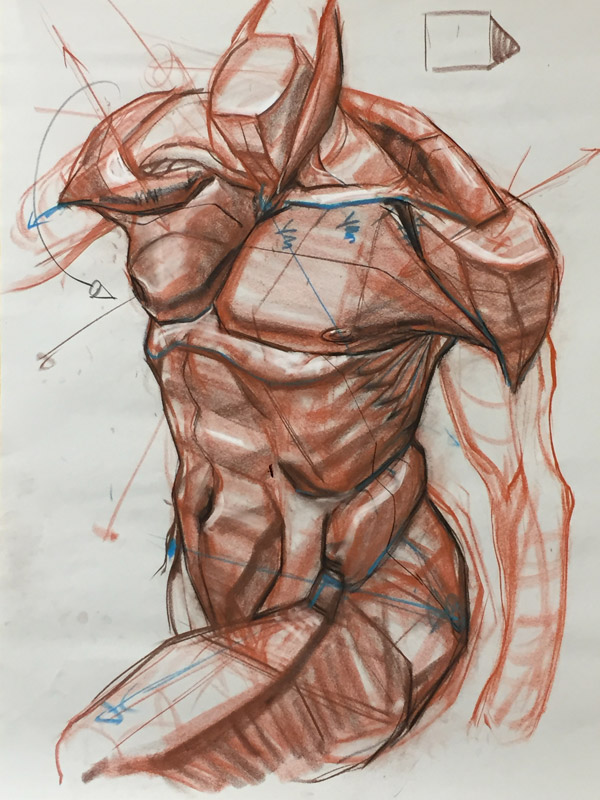

To me, art is generated by two components: the science and the poetry. The science is the foundation such as 2d structures, the light, the value, etc. But, then the poetry comes from the individual. That cannot be taught. The core is foundation. That is what the foundation of artistry means to me. And the art that inspires me is based on design. When I was younger, I was inspired by so many things like the Renaissance and Michael Angelo, and now, I am inspired by design and compositions, like David Hockney.

GW: Can you share details about what you are working on, and what’s exciting you lately?

CH: My final project for 2019 was an art tutorial for the New Masters Academy in Huntington Beach, CA. New Masters Academy gathers local and international talent to record there and I was honored to do a series of painting videos for them.

On a personal note, I have a 2020 project in the works I’m excited about, which is my first book. Recently, at the CTN expo, many people asked me for books. So, I really felt the need to finally get on with it and get a book made! My plan is that the book will be a “How to” on constructive figure drawing. I’m thinking the book will be purely focused on a step by step guide on how to develop a dynamic figure drawing. And then maybe later a second volume that focuses on heads for example, and then a third that focuses on hands, etc. I’m really looking forward to diving deeper in to this project this year. More and more ideas are coming to fruition as I marinate on the inspiration.

GW: After studying at the Art Center College of Design, what was the catalyst that “called you” into teaching?

CH: I really flowed into teaching. When I was a student at the Art Center, I started giving student feedback, and showing others tips and tricks for how to do things. That was really fulfilling and validating. I felt really valued, like I was giving back. And that led to becoming a teacher’s assistant.

Also, at the Art Center, there are workshops where models are booked for art sessions, and they needed someone to supervise while the students came to the class to draw. Plus, at that time, there was only drawing workshops, no painting. So, I was one of the pioneers to start a painting workshop. That initiative led to the Art Center wanting me to continue running that workshop. Even after I graduated, they still wanted me to continue, so they hired me as staff.

I really enjoy teaching and helping people learn, and this experience led to me teaching at Gnomon, and at the Laguna College of Art and Design. I tell all my students that our world is not that big, and I am truly grateful that in my career I have never had to do a single interview. All my work has been on a referral basis. And I believe the reason behind this is because I have a solid foundation. Plus, I work really diligently, and that helps a ton, too! And I try to always have my own approach—a particular style that is recognized and appreciated. My mentors and teachers have been so influential that I try to extend their wisdom into my work. They have all been so generous and I feel that that is key to being a great artist and educator. What I mean by generous is that they have no secrets. Some artists like to hide their approach or keep certain skillsets or shortcuts a secret. But, I feel with the opposite approach, an artist can discover even more through open-sharing, communicating, and experimenting.

GW: You’ve taught at Gnomon since 2005. Is there an experience that stands out to you about teaching at Gnomon that you can share?

CH: What I really like about Gnomon is that the school is very specific. Gnomon focuses on game design and visual effects, so the students have a phenomenal understanding of what the outcome from their education there will be. I have noticed that with other schools that are more broad, the students have a harder time and are not quite sure what they want to do, what classes to take, what to focus on, whether background or characters, etc. But when it comes to Gnomon, their programs are more dense and more specific, so the students know what they are getting in to, which I feel is really great. In addition, I’ve noticed that age-wise, the students at Gnomon seem very mature, and that their focus is spot on, like they are mentally ready for hardcore programs, which make the classes very enjoyable to teach.

GW: Can you describe your approach when teaching foundational classes, such as figure drawing and costume drawing? Including what students should anticipate at this stage?

CH: I approach figure drawing and costume drawing differently. Figure drawing is foundation-focused where costume drawing is design-focused. At the end of the day, every student is a designer. You are going to get paid to design something, or come up with a visual that represents the client’s goal or the need of the project. We put this two-dimensional relationship on paper/surface. And there is a sense of an intense story there, be it violent, or peaceful, or elegance, all based on those shapes.

Figure drawing incorporates a foundational understanding of balance, proportions, shapes, etc., but, then when you get into costumes, and what I love about costumes, is that the models all have different silhouettes. So then our job becomes figuring out all those shapes and how to compose them. That is what is really exciting to me.

GW: What advice do you have for specifically freshman and sophomore students?

CH: Great question. I’ve noticed that new students most often don’t know what they want to do, so I feel solid advice would be to narrow down the focus. It’s important to note that while this new generation is really into games and movies and the whole dramatic look of both industries, it is equally, if not more, important to recognize the foundation part of it all and how much practice and foundational-skill it took to create that.

For example, when I started teaching at Gnomon long ago, the figure drawing class was not a part of their core classes, and therefore at that time, no one was signing up to take the class. It wasn’t until Gnomon added Figure Drawing to their core class structure that students realized the value in that class. Before that, there was a misunderstanding about how important it is. So, often, students would just jump right into classes such as characters, story boarding, environments, etc., but, then they would have a really difficult time in those classes. Because if you don’t understand the foundation elements in producing solid art, or a solid picture, you won’t be able to expand yourself and allow yourself to develop in other intricate areas. If you don’t have the form, it will hold you back.

GW: Can you share what it was like having a mentor like Steve Huston? And how can a student go about finding a mentor?

CH: For sure! I believe having a mentor is like meeting your favorite artist—someone you really admire and wish to be like. In fact, it’s almost as if you don’t really know your inner potential until you meet a mentor who can help you discover that. Throughout my career, I’ve watched many students and colleagues look for a chance to meet their mentor. It may take a while but it is worth the effort. For example, one of my students who is now working at Vouge in Taiwan, posted that her mentor just passed away, but that she was so thankful for the inspiration she garnered from that mentorship. And when I look at my student’s work, I could see right away the inspiration she drew from her mentor. It was really special.

When I was at the Art Center, my first year was my foundation term—all figure drawing and painting classes. My best friend started during the next term and he took a experimental class that ended up really helping him bloom as an artist. He found his mentor and found his talent. I had noticed before that he really succeeded in self-expression, and pop art style, so, when he took that class, he sky-rocketed.

Sometimes an inner skill is discovered when you least expect it, and it can come from anywhere—from a class or a mentor who brings out your inner voice and helps you find your style and strength. And from there, you can also get inspiration and guidance to know where your route should go.

As an artist we tend to like everything. My parents wanted me to work in the entertainment industry, and, at the time, my brother-in-law was working at Warner Bros. When I showed my portfolio to the hiring manager, she asked me to go back and prepare a more entertainment-style-portfolio. But, when I went back to try and do that, everything I drew was still figure related. So, I honestly felt lost. My family wanted me to do this entertainment career, but I loved to draw and paint. At that time I was also teaching, so I went up to my mentor, and I asked him what should I do. I explained about what my family wanted versus what I felt more comfortable with and what I really want to do. He told me straight up that if my heart was not in that field, then I shouldn’t force it, otherwise I was going to be miserable. He told me to imagine how all the other artists will be in the game wholeheartedly, fighting for a position there; and so why try and compete with that when your heart is not there? I ended up taking his advice and I told my family that I wanted to continue down the path I started with figure drawing and painting, and that I wanted to continue teaching. My parents could tell that that was what I truly wanted and thankfully they supported my decision. Today, they are really happy that I’m doing well.

Lastly, I’ll just reiterate again that so much of today’s jobs are by referral, so it is really important to hone your craft and find your voice, and showcase yourself well. If you have the foundation, it will show in your work.

GW: How do you approach teaching the importance of light, color, and angles to produce sophisticated products?

CH: Well, it’s an interesting question, because besides the fact that the proportions need to be accurate, the silhouettes also need to be interesting. And of course the light and shadow separation needs to be clear, so we can get a sense of where the light source is coming from. If we muddy up that separation, then the audience will not be able to read it. And what I mean by clear is that we always want to aim for that point with our work when we can stand ten feet back from our drawing or project, and still see and sense exactly what it should look like.

And then there is half tone (the value that bridges the light to the shadows) like a rendering. It can take hours, weeks, months, depending on how tight you want to render, but it shouldn’t distract either. It shouldn’t distract from what I call a “two-value” difference. Besides the shape being well-designed, the definitions of your structures need to be clear.

And with figures, the biggest component is head, ribcage and pelvis. If an artist doesn’t clearly know that relationship, then the project will feel off, because the audience will always sense that something is off. So, if, for example, the pose is twisting, then the rib cage has to face one direction and the pelvis the other, and of course it has to be absolutely convincing and life-like, too.

GW: Our most heartfelt thanks, Charles, for taking the time to sit down and share with us today. Cheers!

CH: Thank you, Genese Davis, and thank you, Gnomon!

| Check out Anatomy Workshop Volume 7 with Charles Hu |