Babak Bina

Gnomon Workshop instructor Babak Bina has an interesting story to tell. On a journey that's taken him from his home country of Iran to the shores of Canada, he's worked at Double Negative, Method Studios, and Scanline VFX, and has worked on projects ranging from Game of Thrones and Avengers to Star Trek and Wonder Woman.

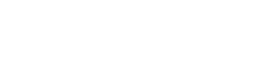

Perhaps his most impressive work is the one project that's wholly his own, though. In 2019, Babak took the plunge and decided to co-write and co-direct his own short film. The result was ‘The Seahorse Trainer,’ a surreal and dreamlike tale driven as much by Babak's imagination as his VFX skillset.

The film screened at over 30 film festivals worldwide and picked up over 15 awards and nominations in the process. Most notably, ‘The Seahorse Trainer’ won Best VFX at SPARK, was honored with the Rising Satar in VFX Award from the VES, and won one of three Jury awards at the Seattle International Film Festival, meaning it qualified for the 2020 Academy Awards.

And yet, as welcome as these accolades were, it was the creative process itself that meant the most to Babak and his team. Read on to learn how Babak motivated himself to believe in and pursue his dream; what he thinks young artists need to know if they're inspired to follow their own indie filmmaking aspirations; and why awards aren't always the sole barometer for success when creating something for yourself.

TGW: Please tell us a little about yourself and your background — how did you get from your initial interest in art to where you are today?

BB: I didn’t realize my potential or interests in art until later on in life, due in part to a poorly planned education system back in my home country of Iran. I originally studied Civil Engineering at university. However, I realized I was not made for such a career and switched to IT, specializing in computer networks.

Around the time I was studying IT in 1998, my path in life steered off in a new direction. I was learning guitar with an instructor who introduced me to the band Tool — a very different type of music than that I was used to, and that would become a significant influence on my life.

I first listened to Tool's album Ænima on a bootlegged, poor-quality cassette tape, and it was as if it cast a spell upon me. I was so intrigued and wanted to decipher what the album was about, so I searched for as much information as possible online — which was not an easy task back then, as I had an unstable dial-up connection, and the internet was much smaller than today.

I found Tool's suggested reading list, which led me to read Carl Jung's Man and His Symbols; I learned about analytical psychology and how art as an expression of our psyche has produced similar motifs in different mythologies. From there, I became interested in the study of comparative mythology, which led me to read Joseph Campbell's The Power of Myth and The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

All of this research, exploration, and soul searching made a significant impact on my life. I decided my calling was to be an artist. Although sculpture was the art form I felt most connected to, I had no background in art, so I just started experimenting on my own: I made abstract, expressive forms out of Play-Doh.

A few years later, around 2003, I applied to and got accepted to a Graphic Design program at a college in Toronto. I had always wanted to emigrate, so in 2004 I packed my two suitcases and left my family in Iran to start my new life as an artist, thousands of kilometers away in Canada.

Once I finished the Graphic Design course, I intended to study sculpture at York University. However, due to financial considerations and learning that academic art education requires studying unrelated material that did not necessarily interest me, I decided to switch to a short 1-year animation program at Seneca College. The whole time I attended Seneca, I spent my free time learning about digital sculpting and using Gnomon Workshop tutorials to teach myself ZBrush.

I finished my course at Seneca and got work at an animation studio, but I'd always wanted to work on visual effects for film. I was lucky enough to receive an offer from Scanline VFX, and once again I packed my two suitcases and left behind my 10-year life in Toronto for Vancouver, which I now call home.

I met my friends Ricardo Bonisoli (co-director of ‘The Seahorse Trainer’) and Holly Pavlik (editor on ‘The Seahorse Trainer’) at Scanline. Together, with our mutual friends Rodmon Sevilla (producer on ‘The Seahorse Trainer’) and Alejandro Mozqueda Torres (animation supervisor on ‘The Seahorse Trainer’), we teamed up to create Rooxter Films and make our first short film, ‘The Seahorse Trainer’.

TGW: What drove you to team up and create Rooxter?

BB: As an artist, I am intrigued by new mediums. Film, as an all-encompassing medium, has always been of particular interest. Just like music, film deals with time, rhythm, and pacing. And just like painting, film can express aesthetics, color, composition, and mood. However, I'd never thought about actually becoming a filmmaker. I felt I lacked the skillset or financial resources required to do something so ambitious and challenging. I created some short stop-motion animated clips purely for fun, but nothing with narrative and story arc.

My mindset changed once I came to Scanline and became more familiar with the filmmaking process. I spoke with my friend Ricardo, and we decided to make a short film together. As visual effects artists, we help execute others' visions every day — and that's undoubtedly rewarding — but we both felt the need to express our own ideas and use our skills as visual effects artists to see that vision through.

Ricardo and I have overlapping interests in fantasy and surrealism, so we decided to make a film that we would both enjoy making but also appreciate as audience members. We hoped our short would act as a treat for those with a taste for surrealism and uniqueness in a world of remakes and formulaic stories.

TGW: Where did the idea for ‘The Seahorse Trainer’ come from?

BB: Ricardo had had the idea for a while: a mockumentary about the fictitious art of seahorse training and an older man who enjoyed this peculiar hobby. The idea seemed odd and magical. After giving it some thought, I suggested we turn the idea into a narrative short instead of a mockumentary; something with a storyline but enough scope for audience interpretation. Filmmakers like David Lynch and the Brothers Quay tell stories that require the viewer's mental and intuitive participation for sense to arise. Those are my favorite types of films — or, more to the point, my favorite kind of art in general. I wanted to replicate this approach in our short film.

Ricardo and I teamed up with Rodmon to write the story. First, we had brainstorming sessions where each of us would bring some ideas to the table. After talking them through, we chose the ideas we all agreed best served the story's core. The process was similar to improvising music with a band; all the dissonant notes slowly came together to form harmony and, eventually, a song.

For me, working through this was an opportunity to shed my fear of filmmaking as an impossible task. I came to realize that while it was challenging, the dream was indeed possible.

TGW: How did you get started on the film?

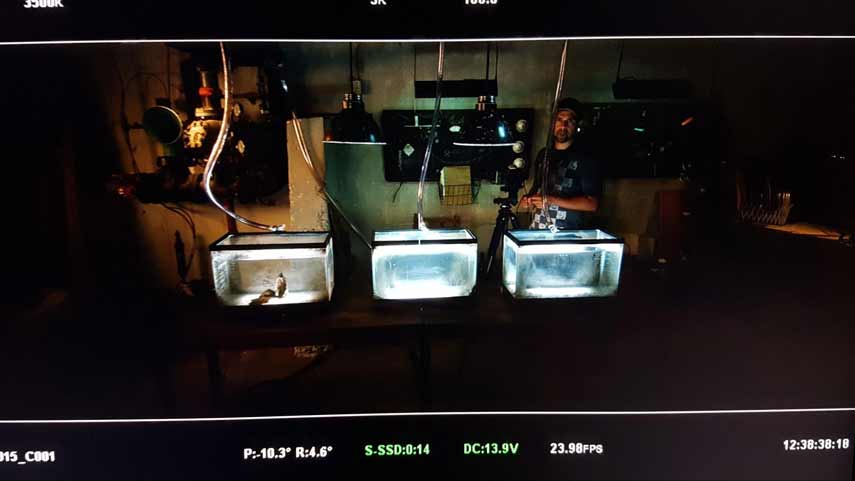

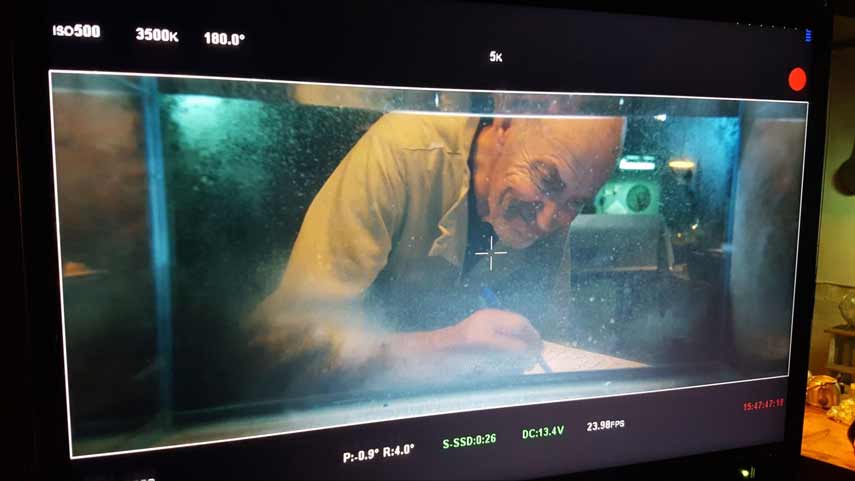

BB: The nature of this short film as a collaborative project required us, as directors, to be on the same page first and foremost. So, with that in mind, we considered everything very carefully during the pre-production phase to ensure our inexperience as directors wouldn't affect efficiency on set. Even before we even started production, we discussed pacing, framing, mood, and everything in between for each shot. We created a lot of concept art, storyboards, and even animatics and used detailed previsualization to communicate our ideas to the crew. I think we played on our strengths, and that was the right thing to do.

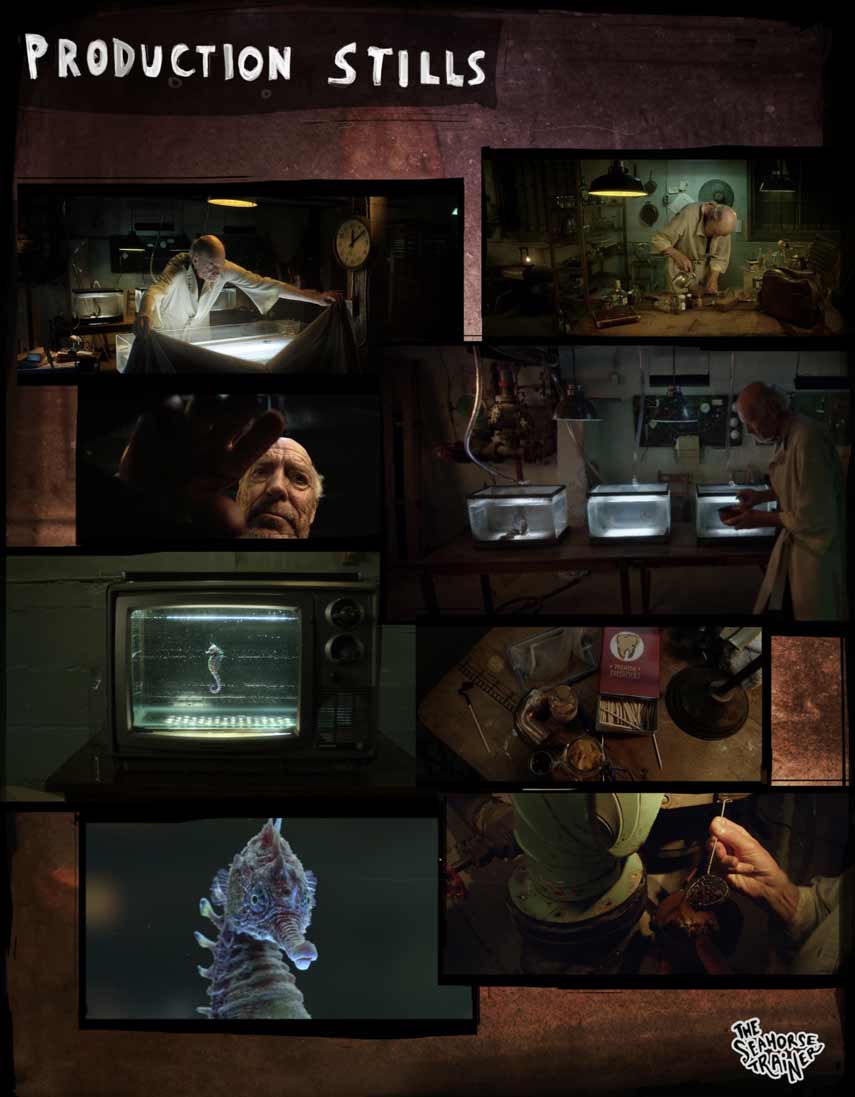

Being so prepared also helped us understand our budget and resource limitations, which allowed us to contain the story within the realm of what was practical. One set, one actor, and multiple CG seahorses seemed manageable.

TGW: What challenges might people face when making their own independent films, and how can they overcome them?

BB: The most significant obstacle is budget — finding people who are willing to invest in your vision is not easy, especially if your project is offbeat, like ‘The Seahorse Trainer.’

To overcome this challenge, we created a comprehensive pitch package. We included all concepts, storyboards, previz, etc., to illustrate our vision and show what we intended to make. Next, we applied to multiple short film grant programs and were thrilled to receive the National Film Board of Canada's Filmmaker Assistance Program award. The award pushed us forward both financially and psychologically. The project started to feel so much more real.

Indiegogo campaigns can also support your indie projects through crowdfunding. We ran an Indiegogo for ‘The Seahorse Trainer,’ which covered a portion of the overall costs.

TGW: What skills do people need who might want to create their own independent film?

BB: If you're making an indie film, experience in multiple aspects of filmmaking is a definite benefit. As you'll likely be working with a small budget, it helps to be hands-on and wear as many hats as you feel confident wearing. Doing so isn't necessarily so you can fill a role you don't have on your team — cinematography or editing, for example — but so you are at least capable of communicating your ideas more effectively with the person in charge through an understanding of their vocabulary and tools.

I think experience in any art discipline helps with filmmaking. If you're a painter, for example, you'll have a solid sense of composition, color, and mood. If you're a musician, you'll bring an understanding of rhythm and pace to your work. In my case, having visual effects experience helped with efficient time management and planning, and as a result, everything went more smoothly during post-production.

Overall, however, I think the most important thing, which often gets overlooked, is having a clear and solid vision of what you want to achieve. From there, it's developing the ability to communicate that vision effectively with your crew.

TGW: How important was it for you as a director to have an understanding of visual effects? Was that knowledge vital to making the film such a success?

BB: We only had one actor, John R. Taylor, who played the role of The Seahorse Trainer. All of the seahorses were computer-generated, as was the levitating black balloon with a jar of teeth attached. As such, ‘The Seahorse Trainer’ relied heavily on visual effects to tell its story.

We designed how the seahorses would look before finding our actor, and doing so helped us in multiple ways. For instance, when talking about lighting with our cinematographer, we had to consider that our main seahorse asset features bioluminescence; having those seahorse assets ready helped us understand how bioluminescence would impact scene setup.

Furthermore, John — who had to act as if the digital seahorses were before his eyes while performing — had a better picture of what he was "interacting" with, thanks to those assets. We would have found all of this more difficult if we couldn't build those seahorse assets upfront.

Considering how visual effects are such an integral part of filmmaking these days, I think it's important for filmmakers to at least be familiar with the VFX process and workflow. Speaking for myself, I do character design, modeling, texturing, and lookdev on blockbusters daily. I have also made a couple of tutorials for the Gnomon Workshop on creature design and modeling/texturing props and characters. I think it's essential to plan your workflow based on your strengths, so that's what I did for ‘The Seahorse Trainer.’

TGW: How important is it for artists to keep their skills sharp and up-to-date if they're hoping to create their own film?

BB: We work in an ever-evolving industry where filmmaking styles, tools, and techniques are constantly changing. Therefore, if you want to stay relevant, you must stay up to date.

Although constantly learning new tools and software can feel like a lot of work, I don’t think it is a bad thing. Software is continually improved to make things easier for us, the users. So, learning the latest and greatest tools is a worthy investment of time, energy, and money, as it will help you become better and more efficient at what you do.

As artists, we tend to find our favorite software, get comfortable using it, and develop a resistance to learning an alternative. However, if you can get past that mindset, the new software you learn might become a favorite in your toolbox and might unlock the skill you need to embark on that personal project you've wanted to work on for years.

TGW: What software did you use for the creation of ‘The Seahorse Trainer’?

BB: We used industry-standard tools: Maya, ZBrush, Mari, V-Ray, and Nuke. For the main seahorse, we modeled in ZBrush using DynaMesh. We didn't concern ourselves with the topology or other technicalities at this stage; we focused solely on design.

After we locked in the design, we took the decimated seahorse model to Maya for topology and UVs and handed it off to rigging and texture/lookdev. Next, we performed some concept color/look tests by painting over a 3D ZBrush render in Photoshop.

Once we had dialed in the look, we created the seahorse textures using procedural and projection tools in Mari and the in-built V-Ray shader. We then passed the seahorse asset back to Maya for shading, lighting, and rendering in V-Ray. We also used V-Ray Fur to enhance the seahorse lookdev by adding microscopic flakes and fuzz, which are only visible when you get very close to the creature.

Finally, we used Nuke for compositing, color correction, and integrating the renders into live-action footage. We also performed color grading in DaVinci Resolve to ensure all shots were consistent and that we achieved the aesthetics we'd been aiming for since the concept stage.

On the production side, we used a combination of Google Docs and frame.io to facilitate shot tracking, reviews, and annotations on artists' work — a sort of indie version of Shotgun.

TGW: What final advice would you give to someone who wants to create their own independent film?

BB: As humans, we're conditioned to evaluate effort by the reward it brings. If something we created receives accolades, financial success, and lots of likes and views on social media, it's considered a success. It has been "worth doing". If the work does not receive those things, it's deemed a failure.

I find this such a negative outlook; it invites fear and doubt and results in stagnancy.

‘The Seahorse Trainer’ was our first short film. The feelings described in the question about the concept being an unachievable "pipe dream" comprised my own internal monologue at one point; I wasn't sure such a thing could ever happen. However, the challenge I overcame was to change perspective: Tell yourself to look at your idea as an opportunity to learn from challenges, rather than just revel in praise, and you can overcome your doubt. You can create to learn, rather than solely to "succeed."

‘The Seahorse Trainer’ did receive several awards and much praise, which of course makes me very happy. However, the most important thing to me is that we did the project at all and that ‘The Seahorse Trainer’ now exists. What happens to the film and how it is received is of secondary importance. Indeed, even if we had not been able to finish ‘The Seahorse Trainer,’ the experience I gained throughout the process of making it would have made the endeavor worthwhile all on its own.

To conclude, my advice is this: If you have a vision that you think the world should see, then consider your skills and resources, find a practical way to express your idea, and do it. If you enjoy the process for the process itself and realize that the experience will make you grow as an artist and a human being, that in itself is the reward for your efforts. If your film gets made, it's a bonus, and if the film receives recognition and awards, that's a double bonus.

But before any of that, get out of your own way and make the film!